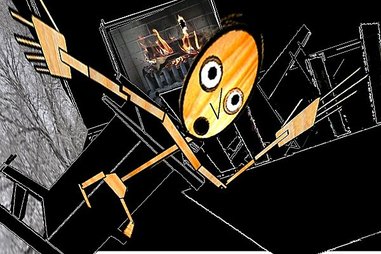

Pine Eyes was written by Martin Bresnick for Zeitgeist in 2006, and was commissioned by and premiered at the Walker Art Center. Pine Eyes is part of Bresnick’s body of work, Opere della Musica Povera (Works of a Poor Music). Begun in 1991, these compositions explore themes of poverty, extremity, and loss. Musically and visually, this concern manifests itself in the determination of all three artists to use limited (impoverished) visual and musical resources to create a work of simplicity, depth, and captivating immediacy. On one level, Pine Eyes is a fantastic tale of transformation and discovery with plenty of bewitchment, thievery, adventure, and heroism typical of a good fairy tale. Delving deeper into Martin Bresnick’s treatment of the tale, it is also an exploration of human nature—our capacity for deceit and treachery as well as our capacity for self-sacrifice and unconditional love.

Pine Eyes by Martin Bresnick

May 20-21, 7:30 p.m

May 22, 2 p.m.

Studio Z: 275 East Fourth Street, Suite 200, Saint Paul

Tickets

Prior to the premiere in 2006, Larry Fuchsberg conducted the following interview with Martin Bresnick about the creation of Pine Eyes.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARTIN BRESNICK

BY LARRY FUCHSBERG, 2006

Larry Fuchsberg: Pine Eyes has had a relatively long gestation, hasn’t it?

Martin Bresnick: Yes. I received the original commission from Zeitgeist in ’98. They wanted a piece that was 15 to 20 minutes in duration, and I proposed doing a version of the Pinocchio story, which I’d been thinking about for a while, that would be just a fragment—an opening, with the hope that someone might find it interesting enough that it could be completed. That’s how the first incarnation of the work came to be, using excerpts from my own translation of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio story, which I renamed Pine Eyes (one possible rendering of the name Pinocchio).

The piece was fun—not exactly a laugh riot, but a sharp revision of the story that carried it far away from the Disney treatment. Zeitgeist and I recorded it, as it then was, for a disc of my music, and we kept on looking for ways to fund the creation of a full-length version. That took a really long time. But now, eight years later, we finally have the evening-length work, with the fortunate addition of visual imagery, which we tried out last year at the Walker.

LF: Why did you make your own translation of Collodi? Were you dissatisfied with existing versions, or was translating a way for you to get closer to the text…?

MB: Both, I think. It wasn’t so much that I was disappointed with previous translations, especially the complete ones, but I was struck by the story, some elements of which have a deeply rooted psychological power that I felt very attracted to. There’s the question of parentage, for example: Who is a true father? In the story, Geppetto isn’t really Pinocchio’s father. Pinocchio doesn’t have a father; he’s just a piece of wood. So the search for a true father, and the finding of someone who, while not the genetic father of this creature, becomes his instructor in how to be human—I was very moved by that, and also by the idea that a creature made of wood could somehow flower into a human being. And then I got interested in the story’s very ambiguous depiction of what it is to be a human being—it’s not always such a great thing!

What particularly stimulated me, though, was my recollection of Disney’s version of the story, which is quite saccharine—not at all like the story I was reading. So I decided that, since I know Italian, I’d go back to the original and find the Pinocchio story I needed to tell—fundamentally, a story about achieving our own authentic humanity. And that’s a very potent and poignant thing.

LF: I have the sense that this work is unusually important to you.

MB: It goes very deep for me, in some ways that I understand and some that I don’t.

LF: Am I right to think that your feelings for Italy are bound up in the piece?

MB: Very much. I lived in Italy twice, saw puppet shows there, and was struck by their crude and vigorous vitality in the commedia dell’arte tradition. Violence was never far beneath the surface of the ancient, ancient stories that the puppets told. Yet the delight that children took in the fantasy and scariness of those stories was unmistakable. Pinocchio is a prime example. In telling of the metamorphosis of one creature into another, it goes back to Ovid and before, but it also contains the Biblical theme of being swallowed by a fish and the castration fantasy of a growing nose that has to be trimmed back. So the story offers a thousand points of departure, all of them rooted deeply in the way we think about the world.

Pine Eyes belongs to a series of pieces I call “Opere della Musica Povera,” or Works of a Poor Music. I think of it as the apotheosis of the series. You can tell very profound and very human stories with the simplest and crudest of materials. Collodi’s book is a masterful illustration of this. There’s a Pinocchio site on the Web that claims that Collodi’s is the second most-read book in the world, after the Bible. I don’t know whether that’s true or not, but for me there’s no doubt that the book is a kind of central text of life.

LF: One of the antecedents of Works of a Poor Music, if I’m not mistaken, is the arte povera movement in the visual arts, which began in Italy in the ’60s.

MB: Yes, I was fortunate enough to see the arte povera movement unfold at first hand and to know some of the artists when I was there in the ’70s. It left a big impact.

LF: Finally, what role has Zeitgeist played in shaping your piece?

MB: I can’t mention Pine Eyes without mentioning Zeitgeist, and in particular I can’t mention this piece without mentioning Eric Stokes, who was a friend from my early twenties onward and who was a model for me as a composer. He was fearless in going against the prevailing modernist culture of his time. He went his own way, towards a music that, like Ives’s, was open to every potential source of musical meaning. It was Eric who stimulated to think about things in that way. And it was he who introduced me to Zeitgeist.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed